Back in junior high, he would spend his days at vintage shops in Koenji. Even when he couldn’t make it to school, there were people there who were “doing what they love,” and that’s where he first heard about Bunka Fashion College and started to picture a path in clothing. The brand Deadbooy is run by this 20-year-old designer.

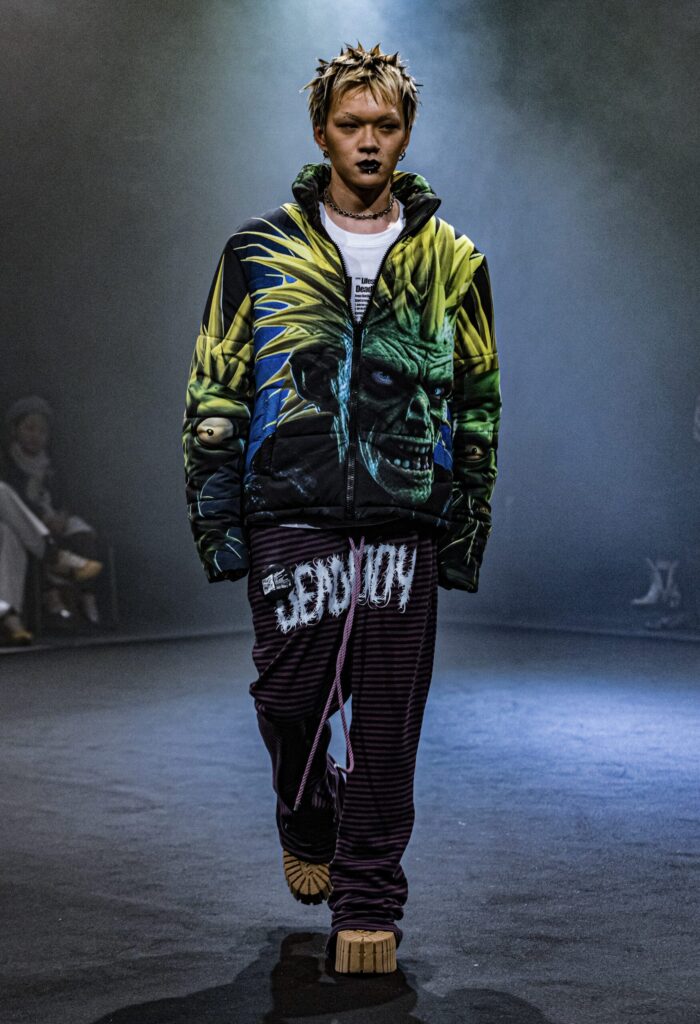

Instead of just holding on to negativity as it is, he wanted to “stay as he is and still turn it into something positive.” He layered that feeling onto the image of a zombie and built his first collection from there. Color palettes where pop and darkness coexist, unexpected combinations of materials, and a strong sense of the body—of clothes that are actually meant to be worn. From talking about garments themselves, to his unease with Tokyo’s fashion and music scenes, to the view he’s aiming for five years from now, he spoke with striking honesty.

-First of all, for people who don’t know the brand yet: what kind of brand is Deadbooy? Could you briefly tell us about the concept and where the name comes from?

Deadbooy: In junior high I went through a pretty rough time with panic disorder and other mental things. Around then I started going to vintage shops in Koenji. I couldn’t go to school, but there were people there who were doing what they love, and I felt comfortable in that space. That’s also where I found out about Bunka Fashion College and thought, maybe I should try to go down the fashion path.

I did go to high school like normal, but I kept thinking, “You only get one shot, so I want to do what I like.” So I enrolled at Bunka and started the brand. I want to be able to turn things that feel negative into something positive without hiding who I really am.

From a place that feels like being “already dead,” coming back to life and crawling up again as a zombie—that’s the meaning behind “Deadbooy.” The first collection also started from that zombie concept.

-Once you decided to be on the making side, what has kept you going this far? What’s the driving force?

Deadbooy: I’ve got a really strong need for approval, and I honestly can’t stand watching other people get praised or achieve stuff (laughs). In high school, my childhood friend went on a dance audition TV show and suddenly everyone was hyping him up, and I just couldn’t accept it. I was like, “No, that should be me.” I definitely have that “me, me, me” side.

If I don’t stand out, I can’t even get on stage, and I can’t keep my cool—so I have to do it. If I were just someone who sits around being jealous, that’d be the end of it, but I’m actually moving and doing things, so in a way it turns into good energy. People like to dress this up when they talk, but I think everyone has some of that in them somewhere.

-If your tags were removed and your pieces were lined up with other brands, what would be the sign that tells people, “This is Deadbooy”?

Deadbooy: The way I use color, and the texture of the fabrics. At first glance things might look big, but when you actually see them they’re really cinched in—surprisingly compact. There’s a slight toy-like feeling; a mix of pop and dark that ends up feeling comfortable.

It’s not so extreme that it’s unwearable, but there’s still an edge. There’s also a sense of “shared coolness” that most people can get behind. That balance is what makes you go, “Yeah, that’s my brand.”

-Then if someone told you, “No color. You can only use black and white,” where would the Deadbooy-ness show up?

Deadbooy: In the graphics. I basically make them myself, using my friends’ faces or photos from fun moments. I stack them on top of each other almost randomly and abstract them. So even in monochrome, I think there’s still a clear way to set myself apart.

And then there’s the “vibe.” Like those T-shirts celebrating someone’s grandma, or those weird ’90s American vintage pieces you don’t really understand. That kind of inside joke—when you look back on it years later and it makes no sense, but that’s what makes it fun.

-When you design, where does the process usually start?

Deadbooy: I start from the concept. Sometimes it’s a seasonal theme, and because I’m still a student, sometimes it comes from a contest or a brief where you have to create “one complete thing.” The collection I’m working on now, for example, is themed around frogs.

For 25AW, because it was right when I’d just started, I wanted to express “coming back to life.” Things that are hard to look at, dirty, distorted—I just threw all of that together. But still with a sense of unity, so that it turns into something cool. That’s what I wanted to express, in life and in clothes.

-You’ve put out some pretty impactful pieces. Do you have a line where you think, “If I go past this, it’s too much”?

Deadbooy: I’m not really into things you can’t wear in daily life. There are pieces on the runway that are huge or don’t fit the body at all, and that’s fine for a show, but clothes are meant to be worn. I’m always conscious of that.

And when something turns into pure “art” to the point of forcing a value system on people, that feels wrong to me. I want there to be room for the person looking at it to imagine things. The main character should be the person wearing it. I want it to make people think, but not force one single interpretation on them.

-What’s the one thing you don’t want to change, no matter how many years go by?

Deadbooy: The idea of “turning dirty, negative things into something positive” is non-negotiable. I also don’t think I’ll ever stop combining materials that “aren’t supposed” to go together. Like mixing popcorn with cut-and-sewn fabric—that kind of feeling is something I want to keep.

-Where do you want to be in five years?

Deadbooy: I want to start a fashion movement that surpasses Paris Fashion Week. I want to do a solo collection show at Tokyo Dome. Fourty thousand people in the audience, to the point where it’s a social phenomenon.

If that happens, I feel like all the unnecessary ties and networks will just fall away. People will come because they want to see it; buyers will show up on their own. It doesn’t have to be a runway in the traditional sense—it could be a more theatrical, total production—but clothes will still be at the center, and everything will expand out from there.

-Have there been any moments recently when you felt, “Yeah, this really paid off”?

Deadbooy: Not long ago, my clothes took me overseas for the first time—two countries, China and Taiwan. Wearing my own brand, eating great food with my friends… having that kind of everyday life through clothes made me really happy.

I won prize money at a contest, took everyone to this amazing Chinese restaurant, and treated them all. We’ve been doing this together since high school, so there was a lot of emotion there. I even wrote them letters. Everyone got emotional and cried. When I first started, I was basically that kid with no friends, so it feels strange that things turned out like this. The best part might be that the brand has given me “friends who are always going to be there.”

-How do you see Tokyo’s fashion scene right now?

Deadbooy: Honestly, I don’t really pay attention to other people, so I don’t know that much. But I do feel like there are a lot of things that are just “too much.” As if being extreme is all that matters. There are a lot of people where I’m like, “Do you actually know clothes?”

I don’t feel like they’re staking their lives on it; I don’t feel any way of life behind it.

Most Japanese designers don’t hit me at all. There’s no momentum—it feels like “edge” that still stays safely on the rails. You make it, you sell it, you profit, and that’s the end. I don’t see what comes after. It makes me think, “There’s no culture in this.”

-On the other hand, which brands do you like?

Deadbooy: I love “99%IS-,” and I basically only own their clothes. Everyone in that team really cherishes the brand. Their friends wear pieces that resell for hundreds of thousands of yen to go out for yakiniku or to festivals—that kind of flex, where you can still feel real everyday life in it, is crazy to me.

There’s this pirate-like feeling—sticking to their own crew, their own inside jokes. They’ll use photos of some local punk band in a kind of parody way; that vibe is so cool. They don’t care about playing it safe. They’re sharp, but still within a range you can actually wear. The way they use color also makes you want to keep collecting the pieces.

View this post on InstagramDeadbooy: I do that on purpose. There are things clothes alone can’t communicate. Clothes aren’t words, so there will always be parts that don’t fully reach people. By working with artists I think are cool, I hope those parts get across. I only offer pieces to people I truly think are cool.

-How do you see Tokyo’s music scene?

Deadbooy: It feels like it’s all about the beat winning. With sampling too—like sampling Vocaloid tracks, which you see a lot—I kind of feel like that “emo” feeling or purity should be created from scratch, you know?

It’s like people are just pouring the emotion of the original song straight into the beat to make it more accessible. If there’s a real conviction behind it, I can still like it, but I feel like a lot of people are getting it wrong. And there are a lot of fakes. I’ve had gifted clothes end up in secondhand shops… There are people whose actions totally contradict what they say. I think there are plenty of people who aren’t really singing about the truth.

Still, I hope more people move out of care for their friends and end up reaching others as something genuine. That goes for anything, not just music.

What he showed, again and again, was a stance of not running away—of staying and protecting what matters. He embraces dirt and distortion without slipping into self-indulgence. Even when his expression gets sharp and extreme, he never cuts the path that leads back from the extraordinary to the everyday. Maybe the reason his talk of “starting a movement” doesn’t sound far-fetched is because, in every word, you can sense how deeply he cares about that physical, lived reality.